Pyotr Stolypin earned a reputation for his harsh crackdown on revolutionary activity and dissent in Russia during his tenure as Prime Minister from 1906 to 1911. His approach to maintaining law and order involved severe measures, including the use of summary executions, which became associated with his name.

Why did Stolypin hang people?

Stolypin’s use of executions was a reaction to the widespread revolutionary activity following the 1905 Russian Revolution. After that uprising, Russia experienced a period of political instability, strikes, peasant revolts, and terrorist attacks against government officials. Revolutionary groups, including socialists, anarchists, and nationalists, were carrying out assassinations, bombings, and uprisings against the Tsarist regime.

Stolypin, believing that the survival of the monarchy was at stake, sought to restore order through a firm crackdown on revolutionaries, insurgents, and political dissidents. His philosophy was that repression and reforms had to go hand in hand—he introduced agrarian reforms to improve the lives of peasants, but at the same time, used repressive methods to crush revolutionary threats. He argued that the state had to act decisively against those who engaged in violence and terror to protect the stability of the empire.

Stolypin’s Military Tribunals and “Stolypin’s necktie”

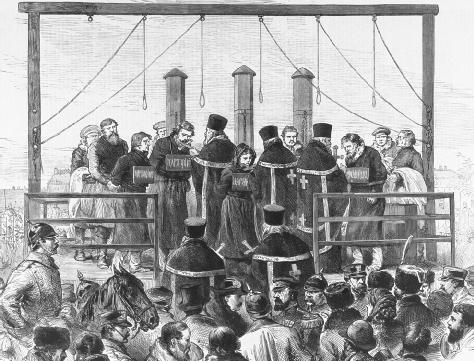

In 1906, Stolypin established military tribunals—special courts with broad powers to try individuals suspected of terrorism and political violence. These tribunals allowed for quick trials and immediate executions, often by hanging. Trials typically lasted only a few days, and the accused had little opportunity to defend themselves.

The summary executions became so frequent that the noose used in these hangings was nicknamed “Stolypin’s necktie.” Stolypin defended these tactics as necessary to prevent anarchy and to ensure the survival of the state.

How many people did Stolypin execute?

Estimates of the number of people executed under Stolypin’s rule vary, but it is generally believed that between 3,000 and 5,000 people were executed by hanging or other means during the period when Stolypin’s tribunals were active (primarily between 1906 and 1909). In addition, many thousands of revolutionaries and dissidents were arrested and exiled to Siberia.

The exact number of those executed is difficult to determine, but Stolypin’s policies created widespread fear among revolutionaries and were intended to be a deterrent against further unrest.

“I want to be buried where I am killed” had Stolypin declared. On September 22 he was laid to rest in Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. After the funeral service the coffin was carried outside the church and lowered next to the historic tomb of another Russian patriot Kochubey.

Stolypin’s Legacy

Stolypin remains a polarizing figure. While he is credited with introducing important agrarian reforms that sought to modernize Russia’s agricultural sector, his legacy is marred by the brutality with which he suppressed political opposition. His use of the death penalty earned him a reputation for ruthlessness, but many within the Russian government saw him as a crucial figure trying to save the Tsarist regime from revolution.